I think investors often lean toward a one-size-fits-all approach to markets. If it worked here, they assume, it should work there too. Obviously, this is not true. One reason is that different markets operate at different levels of efficiency. So, what exactly is market efficiency?

Imagine a farmers’ market where

Everyone knows exactly what each apple is worth

Vendors adjust their prices instantly based on demand

Shoppers move quickly to get the best deals.

There’s no room for overpriced apples - or underpriced ones - because everyone has the same information and acts on it immediately. This is an efficient market.

An efficient stock market is one where every stock's price reflects all available information. If new information comes out, prices adjust quickly, leaving little room for hidden opportunities or outsized profits.

Efficiency doesn’t happen naturally, though. Markets evolve, often after major disruptions that force them to become more transparent and reliable.

The Enron Fiasco: A Catalyst for Market Efficiency

One such disruption was the Enron scandal. My father started his career at Arthur Andersen, an accounting firm with a long history—and a dramatic fall. Enron, one of Andersen’s clients, manipulated its financials to inflate its stock price. When the fraud unraveled, it destroyed the companies and broke investor trust.

This led to the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, a law requiring stricter financial disclosures from public companies. The impact was immediate:

Stock prices became less volatile around earnings announcements.

Investors had better information, reducing surprises.

Markets became more predictable (or at least, less unpredictable)

I’ve heard the Enron story many times now, but only recently did I contextualize how Sarbane’s Oxley shaped the way markets work today.

The tl;dr is markets are efficient because traders, analysts, and institutions are constantly processing information. A company releases earnings? Prices adjust. Interest rates change? Markets react. More transparency, more accuracy.

The speed and accuracy of these adjustments define how efficient a market is.

Why Beating Efficient Markets Is So Difficult

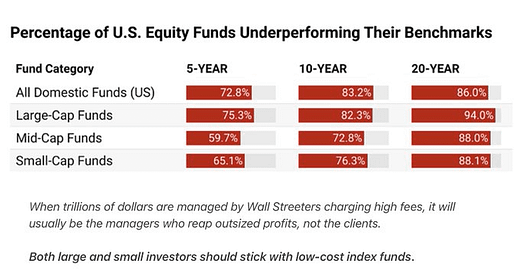

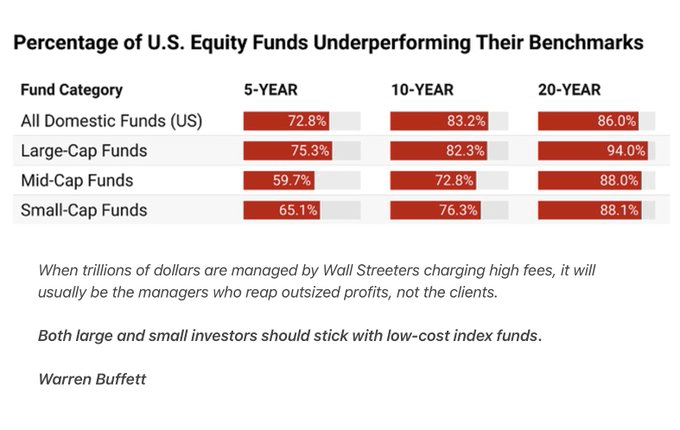

This shift toward efficiency has made beating the market in developed economies like the U.S. extremely hard. Over 90% of active fund managers fail to outperform the S&P 500 over a decade.1 Why? Developed markets are generally dominated by institutions and investors with:

Better data

Faster systems

More experience

More literacy

This makes the market very efficient.

Still, no market is perfect. The dot-com bubble and, more recently, the GameStop saga showed that even efficient markets can be swayed by hype and human behavior.

I think these moments are reminders that markets are made of people, and people aren’t always rational. But outliers are exceptions from the norm: they don’t change the fact that developed markets are tough to beat.

The Opportunity in Developing Markets

In developing markets, the story is different. Challenges like:

Limited information

Cronyism

Financial illiteracy

distort prices in these economies. For those who analyze and act decisively, these inefficiencies do lead to rewards. This creates more opportunities for skilled investors. For example:

India

Large-Cap Funds: About 52% of actively managed large-cap funds fail to outperform their benchmark: S&P BSE 100

Mid and Small-Cap Funds: About 74% of mid and small-cap funds fail to outperform their benchmark: S&P BSE 400 MidSmallCap Index

Japan

About 70% of Japanese equity funds fail to outperform the S&P Japan 500 index

These numbers may not be stellar for most financial advisors, but they’re still a clear improvement over the 90% failure rate among U.S. advisors. However, even this edge is fading. As regulations tighten, tools improve, and financial literacy grows, less-efficient markets are steadily catching up, becoming more efficient over time:

The Bottom Line

For Paasa, the key is understanding the market in and choosing the right strategy where needed.

In efficient markets, we prefer riding the wave with a collection of index funds. Eugene Fama’s work on Efficient Market Hypothesis (Nobel Prize winner) explains why investors should prefer index funds. These funds don’t try to beat the market—they simply match its performance, offering a low-cost, reliable way to invest.2

John Bogle said it best, “Don’t find the needle in the haystack, buy the haystack.”

https://advisor.visualcapitalist.com/success-rate-of-actively-managed-funds/

https://www.investopedia.com/terms/e/efficientmarkethypothesis.asp